"landscape lighting Las Vegas","Unleash the full beauty of landscape lighting Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Best Landscaping Las Vegas Nevada. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape lighting Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"Las Vegas landscape architecture","Achieve remarkable results with Las Vegas landscape architecture. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Expert Landscaping Services in Las Vegas Nevada. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in Las Vegas landscape architecture ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape renovation Las Vegas","Enhance curb appeal via landscape renovation Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape renovation Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"residential landscaping Las Vegas","Immerse yourself in residential landscaping Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in residential landscaping Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"commercial landscaping Las Vegas","Embrace the possibilities with commercial landscaping Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants.

"landscape services Las Vegas","Open the door to landscape services Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape services Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape construction Las Vegas","Elevate your surroundings through landscape construction Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency.

"landscape planning Las Vegas","Experience unparalleled value in landscape planning Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape planning Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape features Las Vegas","Combine style and function in landscape features Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Best Landscaping Nevada USA. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape features Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape elements Las Vegas","Achieve remarkable results with landscape elements Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape elements Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape materials Las Vegas","Optimize your property through landscape materials Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Nevada Las Vegas Landscaping Services. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape materials Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape plants Las Vegas","Embark on a journey toward landscape plants Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape plants Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"drought tolerant landscaping Las Vegas","Open the door to drought tolerant landscaping Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in drought tolerant landscaping Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"sustainable landscaping Las Vegas","Open the door to sustainable landscaping Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in sustainable landscaping Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"eco-friendly landscaping Las Vegas","Maximize every square foot with eco-friendly landscaping Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in eco-friendly landscaping Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"low water landscaping Las Vegas","Open the door to low water landscaping Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in low water landscaping Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"rock landscaping Las Vegas","Embrace the possibilities with rock landscaping Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in rock landscaping Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"gravel landscaping Las Vegas","Embrace the possibilities with gravel landscaping Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in gravel landscaping Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"desert plants Las Vegas","Discover the potential of desert plants Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in desert plants Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"cactus garden Las Vegas","Experience unparalleled value in cactus garden Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat.

"succulent garden Las Vegas","Immerse yourself in succulent garden Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in succulent garden Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024)

|

Artificial turf is a surface of synthetic fibers made to look like natural grass, used in sports arenas, residential lawns and commercial applications that traditionally use grass. It is much more durable than grass and easily maintained without irrigation or trimming, although periodic cleaning is required. Stadiums that are substantially covered and/or at high latitudes often use artificial turf, as they typically lack enough sunlight for photosynthesis and substitutes for solar radiation are prohibitively expensive and energy-intensive. Disadvantages include increased risk of injury especially when used in athletic competition, as well as health and environmental concerns about the petroleum and toxic chemicals used in its manufacture.

Artificial turf first gained substantial attention in 1966, when ChemGrass was installed in the year-old Astrodome, developed by Monsanto and rebranded as AstroTurf, now a generic trademark (registered to a new owner) for any artificial turf.

The first-generation system of shortpile fibers without infill of the 1960s has largely been replaced by two more. The second features longer fibers and sand infill and the third adds recycled crumb rubber to the sand. Compared to earlier systems, modern artificial turf more closely resembles grass in appearance and is also considered safer for athletic competition. However, it is still not widely considered to be equal to grass. Sports clubs, leagues, unions and individual athletes have frequently spoken out and campaigned against it, while local governments have enacted and enforced laws restricting and/or banning its use.

David Chaney, who moved to Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1960 and later served as Dean of the North Carolina State University College of Textiles, headed the team of Research Triangle Park researchers who created the first notable artificial turf. That accomplishment led Sports Illustrated to declare Chaney as the man "responsible for indoor major league baseball and millions of welcome mats."

Artificial turf was first installed in 1964 on a recreation area at the Moses Brown School in Providence, Rhode Island.[1] The material came to public prominence in 1966, when AstroTurf was installed in the Astrodome in Houston, Texas.[1] The state-of-the-art indoor stadium had attempted to use natural grass during its initial season in 1965, but this failed miserably and the field conditions were grossly inadequate during the second half of the season, with the dead grass painted green. Due to a limited supply of the new artificial grass, only the infield was installed before the Houston Astros' home opener in April 1966; the outfield was installed in early summer during an extended Astros road trip and first used after the All-Star Break in July.

The use of AstroTurf and similar surfaces became widespread in the U.S. and Canada in the early 1970s, installed in both indoor and outdoor stadiums used for baseball and football. More than 11,000 artificial turf playing fields have been installed nationally.[2] More than 1,200 were installed in the U.S. in 2013 alone, according to the industry group the Synthetic Turf Council.[2]

Artificial turf was first used in Major League Baseball in the Houston Astrodome in 1966, replacing the grass field used when the stadium opened a year earlier. Even though the grass was specifically bred for indoor use, the dome's semi-transparent Lucite ceiling panels, which had been painted white to cut down on glare that bothered the players, did not pass enough sunlight to support the grass. For most of the 1965 season, the Astros played on green-painted dirt and dead grass.

The solution was to install a new type of artificial grass on the field, ChemGrass, which became known as AstroTurf. Given its early use, the term astroturf has since been genericized as a term for any artificial turf.[3] Because the supply of AstroTurf was still low, only a limited amount was available for the first home game. There was not enough for the entire outfield, but there was enough to cover the traditional grass portion of the infield. The outfield remained painted dirt until after the All-Star Break. The team was sent on an extended road trip before the break, and on 19 July 1966, the installation of the outfield portion of AstroTurf was completed.

The Chicago White Sox became the first team to install artificial turf in an outdoor stadium, as they used it only in the infield and adjacent foul territory at Comiskey Park from 1969 through 1975.[4] Artificial turf was later installed in other new multi-purpose stadiums such as Pittsburgh's Three Rivers Stadium, Philadelphia's Veterans Stadium, and Cincinnati's Riverfront Stadium. Early AstroTurf baseball fields used the traditional all-dirt path, but starting in 1970 with Cincinnati's Riverfront Stadium,[5] teams began using the "base cutout" layout on the diamond, with the only dirt being on the pitcher's mound, batter's circle, and in a five-sided diamond-shaped "sliding box" around each base. With this layout, a painted arc would indicate where the edge of the outfield grass would normally be, to assist fielders in positioning themselves properly. The last stadium in MLB to use this configuration was Rogers Centre in Toronto, when they switched to an all-dirt infield (but keeping the artificial turf) for the 2016 season.[6][7]

The biggest difference in play on artificial turf was that the ball bounced higher than on real grass and also traveled faster, causing infielders to play farther back than they would normally so that they would have sufficient time to react. The ball also had a truer bounce than on grass so that on long throws fielders could deliberately bounce the ball in front of the player they were throwing to, with the certainty that it would travel in a straight line and not be deflected to the right or left. The biggest impact on the game of "turf", as it came to be called, was on the bodies of the players. The artificial surface, which was generally placed over a concrete base, had much less give to it than a traditional dirt and grass field did, which caused more wear-and-tear on knees, ankles, feet, and the lower back, possibly even shortening the careers of those players who played a significant portion of their games on artificial surfaces. Players also complained that the turf was much hotter than grass, sometimes causing the metal spikes to burn their feet or plastic ones to melt. These factors eventually provoked a number of stadiums, such as the Kansas City Royals' Kauffman Stadium, to switch from artificial turf back to natural grass.

In 2000, St. Petersburg's Tropicana Field became the first MLB field to use a third-generation artificial surface, FieldTurf. All other remaining artificial turf stadiums were either converted to third-generation surfaces or were replaced entirely by new natural grass stadiums. In a span of 13 years, between 1992 and 2005, the National League went from having half of its teams using artificial turf to all of them playing on natural grass. With the replacement of Minneapolis's Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome by Target Field in 2010, only two MLB stadiums used artificial turf from 2010 through 2018: Tropicana Field and Toronto's Rogers Centre. This number grew to three when the Arizona Diamondbacks switched Chase Field to artificial turf for the 2019 season; the stadium had grass from its opening in 1998 until 2018, but the difficulty of maintaining the grass in the stadium, which has a retractable roof and is located in a desert city, was cited as the reason for the switch.[8] In 2020, Miami's Marlins Park (now loanDepot Park) also switched to artificial turf for similar reasons, while the Texas Rangers' new Globe Life Field was opened with an artificial surface, as it is also a retractable roof ballpark in a hot weather city; this puts the number of teams using synthetic turf in MLB at five as of 2023.

The first professional American football team to play on artificial turf was the Houston Oilers, then part of the American Football League, who moved into the Astrodome in 1968, which had installed AstroTurf two years prior. In 1969, the University of Pennsylvania's Franklin Field in Philadelphia, at the time also home field of the Philadelphia Eagles, switched from grass to AstroTurf, making it the first National Football League stadium to use artificial turf.

In 2002, CenturyLink Field, originally planned to have a natural grass field, was instead surfaced with FieldTurf upon positive reaction from the Seattle Seahawks when they played on the surface at their temporary home of Husky Stadium during the 2000 and 2001 seasons. This would be the first of a leaguewide trend taking place over the next several seasons that would not only result in teams already using artificial surfaces for their fields switching to the new FieldTurf or other similar surfaces but would also see several teams playing on grass adopt a new surface. (The Indianapolis Colts' RCA Dome and the St. Louis Rams' Edward Jones Dome were the last two stadiums in the NFL to replace their first-generation AstroTurf surfaces for next-generation ones after the 2004 season). For example, after a three-year experiment with a natural surface, Giants Stadium went to FieldTurf for 2003, while M&T Bank Stadium added its own artificial surface the same year (it has since been removed and replaced with a natural surface, which the stadium had before installing the turf). Later examples include Paul Brown Stadium (now Paycor Stadium), which went from grass to turf in 2004; Gillette Stadium, which made the switch in 2006;[9] and NRG Stadium, which did so in 2015. As of 2021, 14 NFL fields out of 30 are artificial. NFL players overwhelmingly prefer natural grass over synthetic surfaces, according to a league survey conducted in 2010. When asked, "Which surface do you think is more likely to shorten your career?", 90% responded artificial turf.[10] When players were asked "Is the Turf versus Grass debate overblown or a real concern"[11] in an anonymous player survey, 83% believe it is a real concern while 12.3% believe it is overblown.

Following receiver Odell Beckham Jr.'s injury during Super Bowl LVI, other NFL players started calling for turf to be banned since the site of the game, SoFi Stadium, was a turf field.[12]

Arena football is played indoors on the older short-pile artificial turf.

The first professional Canadian football stadium to use artificial turf was Empire Stadium in Vancouver, British Columbia, then home of the Canadian Football League's BC Lions, which installed 3M TartanTurf in 1970. Today, eight of the nine stadiums in the CFL currently use artificial turf, largely because of the harsh weather conditions in the latter-half of the season. The only one that does not is BMO Field in Toronto, which initially had an artificial pitch and has been shared by the CFL's Toronto Argonauts since 2016 (part of the endzones at that stadium are covered with artificial turf).[13] The first stadium to use the next-generation surface was Ottawa's Frank Clair Stadium (now TD Place Stadium), which the Ottawa Renegades used when they began play in 2002. The Saskatchewan Roughriders' Taylor Field was the only major professional sports venue in North America to use a second-generation artificial playing surface, Omniturf, which was used from 1988 to 2000, followed by AstroTurf from 2000 to 2007 and FieldTurf from 2007 to its 2016 closure.[14]

Some cricket pitches are made of synthetic grass[15] or of a hybrid of mostly natural and some artificial grass, with these "hybrid pitches" having been implemented across several parts of the United Kingdom[16] and Australia.[17] The first synthetic turf cricket field in the USA was opened in Fremont, California in 2016.[18]

The introduction of synthetic surfaces has significantly changed the sport of field hockey. Since being introduced in the 1970s, competitions in western countries are now mostly played on artificial surfaces. This has increased the speed of the game considerably and changed the shape of hockey sticks to allow for different techniques, such as reverse stick trapping and hitting.

Field hockey artificial turf differs from artificial turf for other sports, in that it does not try to reproduce a grass feel, being made of shorter fibers. This allows the improvement in speed brought by earlier artificial turfs to be retained. This development is problematic for areas which cannot afford to build an extra artificial field for hockey alone. The International Hockey Federation and manufacturers are driving research in order to produce new fields that will be suitable for a variety of sports.

The use of artificial turf in conjunction with changes in the game's rules (e.g., the removal of offside, introduction of rolling substitutes and the self-pass, and to the interpretation of obstruction) have contributed significantly to change the nature of the game, greatly increasing the speed and intensity of play as well as placing far greater demands on the conditioning of the players.

Some association football clubs in Europe installed synthetic surfaces in the 1980s, which were called "plastic pitches" (often derisively) in countries such as England. There, four professional club venues had adopted them; Queens Park Rangers's Loftus Road (1981–1988), Luton Town's Kenilworth Road (1985–1991), Oldham Athletic's Boundary Park (1986–1991) and Preston North End's Deepdale (1986–1994). QPR had been the first team to install an artificial pitch at their stadium in 1981, but were the first to remove it when they did so in 1988. Artificial pitches were banned from top-flight (then First Division) football in 1991, forcing Oldham Athletic to remove their artificial pitch after their promotion to the First Division in 1991, while then top-flight Luton Town also removed their artificial pitch at the same time. The last Football League team to have an artificial pitch in England was Preston North End, who removed their pitch in 1994 after eight years in use. Artificial pitches were banned from the top four divisions from 1995.

Artificial turf gained a bad reputation[neutrality is disputed] globally, with fans and especially with players. The first-generation artificial turf surfaces were carpet-like in their look and feel, and thus, a far harder surface than grass and soon became known[by whom?] as an unforgiving playing surface that was prone to cause more injuries, and in particular, more serious joint injuries, than would comparatively be suffered on a grass surface. This turf was also regarded as aesthetically unappealing to many fans[weasel words].

In 1981, London football club Queens Park Rangers dug up its grass pitch and installed an artificial one. Others followed, and by the mid-1980s there were four artificial surfaces in operation in the English league. They soon became a national joke: the ball pinged round like it was made of rubber, the players kept losing their footing, and anyone who fell over risked carpet burns. Unsurprisingly, fans complained that the football was awful to watch and, one by one, the clubs returned to natural grass.[19]

In the 1990s, many North American soccer clubs also removed their artificial surfaces and re-installed grass, while others moved to new stadiums with state-of-the-art grass surfaces that were designed to withstand cold temperatures where the climate demanded it. The use of artificial turf was later banned by FIFA, UEFA and by many domestic football associations, though, in recent years,[when?] both governing bodies have expressed resurrected interest in the use of artificial surfaces in competition, provided that they are FIFA Recommended. UEFA has now been heavily involved in programs to test artificial turf, with tests made in several grounds meeting with FIFA approval. A team of UEFA, FIFA and German company Polytan conducted tests in the Stadion Salzburg Wals-Siezenheim in Salzburg, Austria which had matches played on it in UEFA Euro 2008. It is the second FIFA 2 Star approved artificial turf in a European domestic top flight, after Dutch club Heracles Almelo received the FIFA certificate in August 2005.[20] The tests were approved.[21]

FIFA originally launched its FIFA Quality Concept in February 2001. UEFA announced that starting from the 2005–06 season, approved artificial surfaces were to be permitted in their competitions.

A full international fixture for the 2008 European Championships was played on 17 October 2007 between England and Russia on an artificial surface, which was installed to counteract adverse weather conditions, at the Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow.[22][23] It was one of the first full international games to be played on such a surface approved by FIFA and UEFA. The latter ordered the 2008 European Champions League final hosted in the same stadium in May 2008 to place on grass, so a temporary natural grass field was installed just for the final.

UEFA stressed that artificial turf should only be considered an option where climatic conditions necessitate.[24] One Desso "hybrid grass" product incorporates both natural grass and artificial elements.[25]

In June 2009, following a match played at Estadio Ricardo Saprissa in Costa Rica, American national team manager Bob Bradley called on FIFA to "have some courage" and ban artificial surfaces.

FIFA designated a star system for artificial turf fields that have undergone a series of tests that examine quality and performance based on a two star system.[26] Recommended two-star fields may be used for FIFA Final Round Competitions as well as for UEFA Europa League and Champions League matches.[27] There are currently 130 FIFA Recommended 2-Star installations in the world.[28]

In 2009, FIFA launched the Preferred Producer Initiative to improve the quality of artificial football turf at each stage of the life cycle (manufacturing, installation and maintenance).[29] Currently, there are five manufacturers that were selected by FIFA: Act Global, Limonta, Desso, GreenFields, and Edel Grass. These firms have made quality guarantees directly to FIFA and have agreed to increased research and development.

In 2010, Estadio Omnilife with an artificial turf opened in Guadalajara to be the new home of Chivas, one of the most popular teams in Mexico. The owner of Chivas, Jorge Vergara, defended the reasoning behind using artificial turf because the stadium was designed to be "environment friendly and as such, having grass would result [in] using too much water."[30] Some players criticized the field, saying its harder surface caused many injuries. When Johan Cruyff became the adviser of the team, he recommended the switch to natural grass, which the team did in 2012.[31]

In November 2011, it was reported that a number of English football clubs were interested in using artificial pitches again on economic grounds.[32] As of January 2020, artificial pitches are not permitted in the Premier League or Football League but are permitted in the National League and lower divisions. Bromley are an example of an English football club who currently use a third-generation artificial pitch.[33] In 2018, Sutton United were close to achieving promotion to the Football League and the debate in England about artificial pitches resurfaced again. It was reported that, if Sutton won promotion, they would subsequently be demoted two leagues if they refused to replace their pitch with natural grass.[34] After Harrogate Town's promotion to the Football League in 2020, the club was obliged to install a natural grass pitch at Wetherby Road;[35] and after winning promotion in 2021 Sutton Utd were also obliged to tear up their artificial pitch and replace it with grass, at a cost of more than £500,000.[36] Artificial pitches are permitted in all rounds of the FA Cup competition.

The 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup took place entirely on artificial surfaces, as the event was played in Canada, where almost all of the country's stadiums use artificial turf due to climate issues. This plan garnered criticism from players and fans, some believing the artificial surfaces make players more susceptible to injuries. Over fifty of the female athletes protested against the use of artificial turf on the basis of gender discrimination.[37][38] Australia winger Caitlin Foord said that after playing 90 minutes there was no difference to her post-match recovery – a view shared by the rest of the squad. The squad spent much time preparing on the surface and had no problems with its use in Winnipeg. "We've been training on [artificial] turf pretty much all year so I think we're kind of used to it in that way ... I think grass or turf you can still pull up sore after a game so it's definitely about getting the recovery in and getting it right", Foord said.[39] A lawsuit was filed on 1 October 2014 in an Ontario tribunal court by a group of women's international soccer players against FIFA and the Canadian Soccer Association and specifically points out that in 1994 FIFA spent $2 million to plant natural grass over artificial turf in New Jersey and Detroit.[40] Various celebrities showed their support for the women soccer players in defense of their lawsuit, including actor Tom Hanks, NBA player Kobe Bryant and U.S. men's soccer team keeper Tim Howard. Even with the possibility of boycotts, FIFA's head of women's competitions, Tatjana Haenni, made it clear that "we play on artificial turf and there's no Plan B."[41][42]

The first stadium to use artificial turf in Brazil was Atlético Paranaense's Arena da Baixada in 2016. In 2020, the administration of Allianz Parque, home of Sociedade Esportiva Palmeiras, started the implementation of the second artificial pitch in the country.[43]

Rugby union also uses artificial surfaces at a professional level. Infill fields are used by English Premiership Rugby teams Gloucester, Newcastle Falcons, Saracens F.C. and the now defunct Worcester Warriors, as well as United Rugby Championship teams Cardiff, Edinburgh and Glasgow Warriors. Some fields, including Twickenham Stadium, have incorporated a hybrid field, with grass and synthetic fibers used on the surface. This allows for the field to be much more hard wearing, making it less susceptible to weather conditions and frequent use.

Carpet has been used as a surface for indoor tennis courts for decades, though the first carpets used were more similar to home carpets than a synthetic grass. After the introduction of AstroTurf, it came to be used for tennis courts, both indoor and outdoor, though only a small minority of courts use the surface.[44][45] Both infill and non-infill versions are used, and are typically considered medium-fast to fast surfaces under the International Tennis Federation's classification scheme.[44] A distinct form found in tennis is an "artificial clay" surface,[44] which seeks to simulate a clay court by using a very short pile carpet with an infill of the same loose aggregate used for clay courts that rises above the carpet fibers.[44]

Tennis courts such as Wimbledon are considering using an artificial hybrid grass to replace their natural lawn courts. Such systems incorporate synthetic fibers into natural grass to create a more durable surface on which to play.[46] Such hybrid surfaces are currently used for some association football stadiums, including Wembley Stadium.

Synthetic turf can also be used in the golf industry, such as on driving ranges, putting greens and even in some circumstances tee boxes. For low budget courses, particularly those catering to casual golfers, synthetic putting greens offer the advantage of being a relatively cheap alternative to installing and maintaining grass greens, but are much more similar to real grass in appearance and feel compared to sand greens which are the traditional alternative surface. Because of the vast areas of golf courses and the damage from clubs during shots, it is not feasible to surface fairways with artificial turf.

Artificial grass is used to line the perimeter of some sections of some motor circuits, and offers less grip than some other surfaces.[47] It can pose an obstacle to drivers if it gets caught on their car.[48]

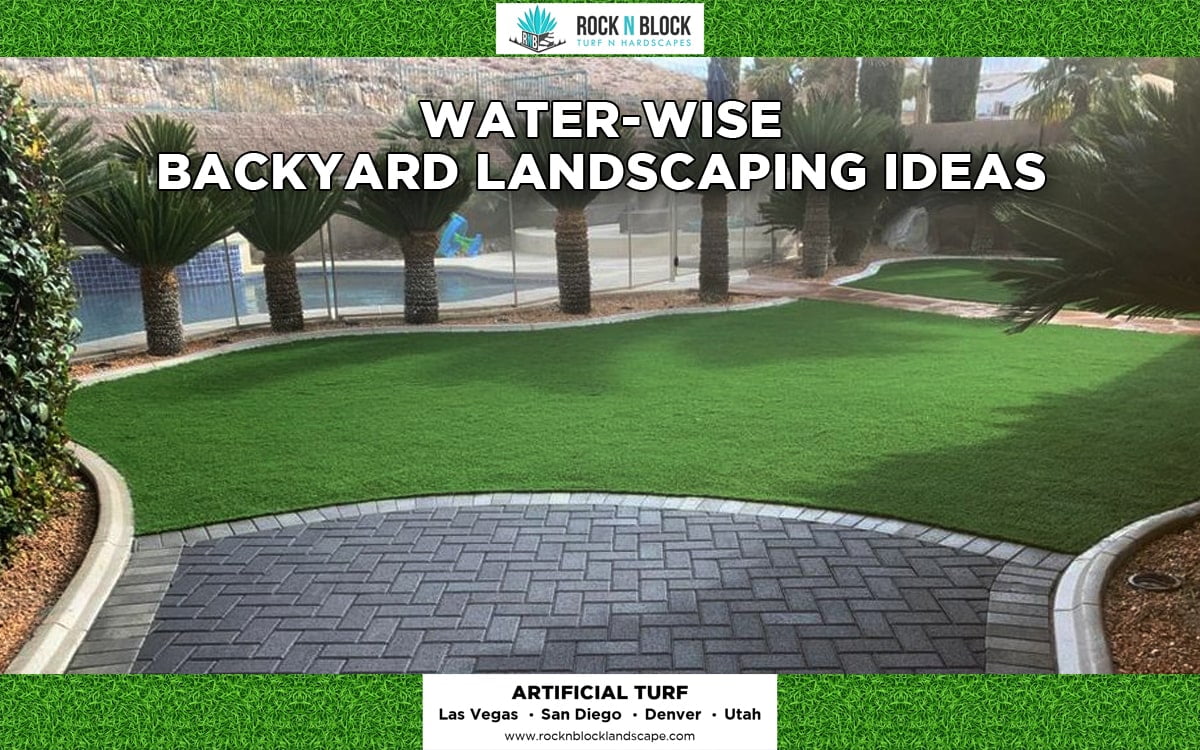

Since the early 1990s, the use of synthetic grass in the more arid western states of the United States has moved beyond athletic fields to residential and commercial landscaping.[49] New water saving programs, as of 2019, which grant rebates for turf removal, do not accept artificial turf as replacement and require a minimum of plants.[50][51]

The use of artificial grass for convenience sometimes faces opposition: Legislation frequently seeks to preserve natural gardens and fully water permeable surfaces, therefore restricting the use of hardscape and plantless areas, including artificial turf. In several locations in different countries, homeowners have been fined, ordered to remove artificial turf and/or had to defend themselves in courts. Many of these restrictions can be found in local bylaws and ordinances. These not always applied in a consistent manner,[52][53][54] especially in municipalities that utilize a complaint-based model for enforcing local laws.

Sunlight reflections from nearby windows can cause artificial turf to melt. This can be avoided by adding perforated vinyl privacy window film adhesive to the outside of the window causing the reflection.

Artificial turf has been used at airports.[55] Here it provides several advantages over natural turf – it does not support wildlife, it has high visual contrast with runways in all seasons, it reduces foreign object damage (FOD) since the surface has no rocks or clumps, and it drains well.[56]

Some artificial turf systems allow for the integration of fiber-optic fibers into the turf. This would allow for runway lighting to be embedded in artificial landing surfaces for aircraft (or lighting or advertisements to be directly embedded in a playing surface).[57]

Artificial turf is commonly used for tanks containing octopusses, in particular the Giant Pacific octopus since it is a reliable way to prevent the octopusses from escaping their tank, as they prevent the suction cups on the tentacles from getting a tight seal.[58]

The first major academic review of the environmental and health risks and benefits of artificial turf was published in 2014;[59] it was followed by extensive research on possible risks to human health, but holistic analyses of the environmental footprint of artificial turf compared with natural turf only began to emerge in the 2020s,[60][61] and frameworks to support informed policymaking were still lacking.[62][63] Evaluating the relative environmental footprints of natural and artificial turf is complex, with outcomes depending on a wide range of factors, including (to give the example of a sports field):[59]

Artificial turf has been shown to contribute to global warming by absorbing significantly more radiation than living turf and, to a lesser extent, by displacing living plants that could sequester carbon dioxide through photosynthesis;[64] a study at New Mexico State University found that in that environment, water-cooling of artificial turf can demand as much water as natural turf.[65] However, a 2022 study that used real-world data to model a ten-year-life-cycle environmental footprint for a new natural-turf soccer field compared with an artificial-turf field found that the natural-turf field contributed twice as much to global warming as the artificial one (largely due to a more resource-intensive construction phase), while finding that the artificial turf would likely cause more pollution of other kinds. It promoted improvements to usual practice such as the substitution of cork for rubber in artificial pitches and more drought-resistant grasses and electric mowing in natural ones.[60] In 2021, a Zurich University of Applied Sciences study for the city of Zurich, using local data on extant pitches, found that, per hour of use, natural turf had the lowest environmental footprint, followed by artificial turf with no infill, and then artificial turf using an infill (e.g. granulated rubber). However, because it could tolerate more hours of use, unfilled artificial turf often had the lowest environmental footprint in practice, by reducing the total number of pitches required. The study recommended optimising the use of existing pitches before building new ones, and choosing the best surface for the likely intensity of use.[61] Another suggestion is the introduction of green roofs to offset the conversion of grassland to artificial turf.[66]

Contrary to popular belief, artificial turf is not maintenance free. It requires regular maintenance, such as raking and patching, to keep it functional and safe.[67]

Some artificial turf uses infill such as silicon sand, but most uses granulated rubber, referred to as "crumb rubber". Granulated rubber can be made from recycled car tires and may carry heavy metals, PFAS chemicals, and other chemicals of environmental concern. The synthetic fibers of artificial turf are also subject to degradation. Thus chemicals from artificial turfs leach into the environment, and artificial turf is a source of microplastics pollution and rubber pollution in air, fresh-water, sea and soil environments.[68][69][70][71][72][73][59][excessive citations] In Norway, Sweden, and at least some other places, the rubber granulate from artificial turf infill constitutes the second largest source of microplastics in the environment after the tire and road wear particles that make up a large portion of the fine road debris.[74][75][76] As early as 2007, Environment and Human Health, Inc., a lobby-group, proposed a moratorium on the use of ground-up rubber tires in fields and playgrounds based on health concerns;[77] in September 2022, the European Commission made a draft proposal to restrict the use of microplastic granules as infill in sports fields.[78]

What is less clear is how likely this pollution is in practice to harm humans or other organisms and whether these environmental costs outweigh the benefits of artificial turf, with many scientific papers and government agencies (such as the United States Environmental Protection Agency) calling for more research.[2] A 2018 study published in Water, Air, & Soil Pollution analyzed the chemicals found in samples of tire crumbs, some used to install school athletic fields, and identified 92 chemicals only about half of which had ever been studied for their health effects and some of which are known to be carcinogenic or irritants. It stated "caution would argue against use of these materials where human exposure is likely, and this is especially true for playgrounds and athletic playing fields where young people may be affected".[79] Conversely, a 2017 study in Sports Medicine argued that "regular physical activity during adolescence and early adulthood helps prevent cancer later in life. Restricting the use or availability of all-weather year-round synthetic fields and thereby potentially reducing exercise could, in the long run, actually increase cancer incidence, as well as cardiovascular disease and other chronic illnesses."[80]

The possibility that carcinogenic substances in artificial turf could increase risks of human cancer (the artificial turf–cancer hypothesis) gained a particularly high profile in the first decades of the twenty-first century and attracted extensive study, with scientific reports around 2020 finding cancer-risks in modern artificial turf negligible.[81][82][83][84] But concerns have extended to other human-health risks, such as endocrine disruption that might affect early puberty, obesity, and children's attention spans.[85][86][87][88] Potential harm to fish[70] and earthworm[89] populations has also been shown.

A study for the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection analyzed lead and other metals in dust kicked into the air by physical activity on five artificial turf fields. The results suggest that even low levels of activity on the field can cause particulate matter containing these chemicals to get into the air where it can be inhaled and be harmful. The authors state that since no level of lead exposure is considered safe for children, "only a comprehensive mandated testing of fields can provide assurance that no health hazard on these fields exists from lead or other metals used in their construction and maintenance."[90]

A number of health and safety concerns have been raised about artificial turf.[2] Friction between skin and older generations of artificial turf can cause abrasions and/or burns to a much greater extent than natural grass.[91] Artificial turf tends to retain heat from the sun and can be much hotter than natural grass with prolonged exposure to the sun.[92]

There is some evidence that periodic disinfection of artificial turf is required as pathogens are not broken down by natural processes in the same manner as natural grass. Despite this, a 2006 study suggests certain microbial life is less active in artificial turf.[91]

There is evidence showing higher rates of player injury on artificial turf. By November 1971, the injury toll on first-generation artificial turf had reached a threshold that resulted in congressional hearings by the House subcommittee on commerce and finance.[93][94][95] In a study performed by the National Football League Injury and Safety Panel, published in the October 2012 issue of the American Journal of Sports Medicine, Elliott B. Hershman et al. reviewed injury data from NFL games played between 2000 and 2009, finding that "the injury rate of knee sprains as a whole was 22% higher on FieldTurf than on natural grass. While MCL sprains did not occur at a rate significantly higher than on grass, rates of ACL sprains were 67% higher on FieldTurf."[96] Metatarsophalangeal joint sprain, known as "turf toe" when the big toe is involved, is named from the injury being associated with playing sports on rigid surfaces such as artificial turf and is a fairly common injury among professional American football players. Artificial turf is a harder surface than grass and does not have much "give" when forces are placed on it.[97]

This sense of the word has come to be frequently used as a generic term for any artificial turf (in the same way that other brand names have been genericized, such as xerox). When used this way, it's often seen in lowercase (astroturf).

It was the first stadium to include dirt sliding pits around each base, something that has become standard in every turf baseball field built since.

cite web: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)In 1988, the Roughriders replaced the first artificial turf with a new type of system called OmniTurf. Unlike AstroTurf, OmniTurf was an inlay turf system, which relied on 300 tons of sand to hold it in place (rather than the traditional glued-down system). Over the years, a number of problems occurred with this system and it eventually became necessary to replace it prior to its usable age being reached.

The major concerns stem from the infill material that is typically derived from scrap tires. Tire rubber crumb contains a range of organic contaminants and heavy metals that can volatilize into the air and/or leach into the percolating rainwater, thereby posing a potential risk to the environment and human health.

Microplastics are increasingly seen as an environmental problem of global proportions. While the focus to date has been on microplastics in the ocean and their effects on marine life, microplastics in soils have largely been overlooked. Researchers are concerned about the lack of knowledge regarding potential consequences of microplastics in agricultural landscapes from application of sewage sludge.

researchers have ranked the sources of microplastic particles by size. The amount of microplastic particles emitted by traffic is estimated to 13 500 tonnes per year. Artificial turf ranks as the second largest source of emissions and is responsible for approximately 2300-3900 tonnes per year.

cite journal: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)cite journal: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)![]() This article incorporates text by National Center for Health Research available under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license. The text and its release have been received by the Wikimedia Volunteer Response Team

This article incorporates text by National Center for Health Research available under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license. The text and its release have been received by the Wikimedia Volunteer Response Team

.

|

|

This article possibly contains original research. (July 2016)

|

A lawn (/lÉâ€ÂÂÂËÂÂÂÂn/) is an area of soil-covered land planted with grasses and other durable plants such as clover which are maintained at a short height with a lawn mower (or sometimes grazing animals) and used for aesthetic and recreational purposes—it is also commonly referred to as part of a garden. Lawns are usually composed only of grass species, subject to weed and pest control, maintained in a green color (e.g., by watering), and are regularly mowed to ensure an acceptable length.[1] Lawns are used around houses, apartments, commercial buildings and offices. Many city parks also have large lawn areas. In recreational contexts, the specialised names turf, parade, pitch, field or green may be used, depending on the sport and the continent.

The term "lawn", referring to a managed grass space, dates to at least the 16th century. With suburban expansion, the lawn has become culturally ingrained in some areas of the world as part of the desired household aesthetic.[2] However, awareness of the negative environmental impact of this ideal is growing.[3] In some jurisdictions where there are water shortages, local government authorities are encouraging alternatives to lawns to reduce water use. Researchers in the United States have noted that suburban lawns are "biological deserts" that are contributing to a "continental-scale ecological homogenization."[4] Lawn maintenance practices also cause biodiversity loss in surrounding areas.[5][6] Some forms of lawn, such as tapestry lawns, are designed partly for biodiversity and pollinator support.

Lawn is a cognate of Welsh llan ( Cornish and Breton *lann* which is derived from the Common Brittonic word landa (Old French: lande) that originally meant heath, barren land, or clearing.[7][8]

Areas of grass grazed regularly by rabbits, horses or sheep over a long period often form a very low, tight sward similar to a modern lawn. This was the original meaning of the word "lawn", and the term can still be found in place names. Some forest areas where extensive grazing is practiced still have these seminatural lawns. For example, in the New Forest, England, such grazed areas are common, and are known as lawns, for example Balmer Lawn.[citation needed]

Lawns may have originated as grassed enclosures within early medieval settlements used for communal grazing of livestock, as distinct from fields reserved for agriculture.[citation needed] Low, mown-meadow areas may also have been valued because they allowed those inside an enclosed fence or castle to view those approaching. The early lawns were not always distinguishable from pasture fields. The damp climate of maritime Western Europe in the north made lawns possible to grow and manage. They were not a part of gardens in most other regions and cultures of the world until contemporary influence.[9]

In 1100s Britain, low-growing area of grasses and meadow flowers were grazed or scythed to keep them short, and used for sport.[10] Lawn bowling, which began in the 12th or 13th century, required short turf.[10]

Establishing grass using sod instead of seed was first documented in a Japanese text of 1159.[10]

Lawns became popular with the aristocracy in northern Europe from the Middle Ages onward. In the fourteen hundreds, open expanses of low grasses appear in paintings of public and private areas; by the fifteen hundreds, such areas were found in the gardens of the wealthy across northern and central Europe. Public meadow areas, kept short by sheep, were used for new sports such as cricket, soccer, and golf.[10] The word "laune" is first attested in 1540 from the Old French lande "heath, moor, barren land; clearing".[11] It initially described a natural opening in a woodland.[10] In the sixteen hundreds, "lawn" came to mean a grassy stretch of untilled land, and by mid-century, there were publications on seeding and transplanting sod. In the seventeen hundreds, "lawn" came to mean specifically a mown stretch of meadow.[10]

Lawns similar to those of today first appeared in France and England in the 1700s when André Le Nôtre designed the gardens of the Palace of Versailles that included a small area of grass called the tapis vert, or "green carpet", which became a common feature of French gardens. Large, mown open spaces became popular in Europe and North America.[10] The lawn was influenced by later seventeen-hundreds trends replicating the romantic aestheticism of grassy pastoralism from Italian landscape paintings.[12]

Before the invention of mowing machines in 1830, lawns were managed very differently. They were an element of wealthy estates and manor houses, and in some places were maintained by labor-intensive scything and shearing (for hay or silage). They were also pasture land maintained through grazing by sheep or other livestock.[citation needed]

It was not until the 17th and 18th century that the garden and the lawn became a place created first as walkways and social areas. They were made up of meadow plants, such as camomile, a particular favourite (see camomile lawn). In the early 17th century, the Jacobean epoch of gardening began; during this period, the closely cut "English" lawn was born. By the end of this period, the English lawn was a symbol of status of the aristocracy and gentry.[citation needed]

In the early 18th century, landscape gardening for the aristocracy entered a golden age, under the direction of William Kent and Lancelot "Capability" Brown. They refined the English landscape garden style with the design of natural, or "romantic", estate settings for wealthy Englishmen.[13] Brown, remembered as "England's greatest gardener", designed over 170 parks, many of which still endure. His influence was so great that the contributions to the English garden made by his predecessors Charles Bridgeman and William Kent are often overlooked.[14]

His work still endures at Croome Court (where he also designed the house), Blenheim Palace, Warwick Castle, Harewood House, Bowood House, Milton Abbey (and nearby Milton Abbas village), in traces at Kew Gardens and many other locations.[15] His style of smooth undulating lawns which ran seamlessly to the house and meadow, clumps, belts and scattering of trees and his serpentine lakes formed by invisibly damming small rivers, were a new style within the English landscape, a "gardenless" form of landscape gardening, which swept away almost all the remnants of previous formally patterned styles. His landscapes were fundamentally different from what they replaced, the well-known formal gardens of England which were criticised by Alexander Pope and others from the 1710s.[16]

The open "English style" of parkland first spread across Britain and Ireland, and then across Europe, such as the garden à la française being replaced by the French landscape garden. By this time, the word "lawn" in England had semantically shifted to describe a piece of a garden covered with grass and closely mown.[17]

Wealthy families in America during the late 18th century also began mimicking English landscaping styles. British settlers in North America imported an affinity for landscapes in the style of the English lawn. However, early in the colonization of the continent, environments with thick, low-growing, grass-dominated vegetation were rare in the eastern part of the continent, enough so that settlers were warned that it would be difficult to find land suitable for grazing cattle.[18] In 1780, the Shaker community began the first industrial production of high-quality grass seed in North America, and a number of seed companies and nurseries were founded in Philadelphia. The increased availability of these grasses meant they were in plentiful supply for parks and residential areas, not just livestock.[17]

Thomas Jefferson has long been given credit for being the first person to attempt an English-style lawn at his estate, Monticello, in 1806, but many others had tried to emulate English landscaping before he did. Over time, an increasing number towns in New England began to emphasize grass spaces. Many scholars link this development to the romantic and transcendentalist movements of the 19th century. These green commons were also heavily associated with the success of the Revolutionary War and often became the homes of patriotic war memorials after the Civil War ended in 1865.[17]

Before the mechanical lawn mower, the upkeep of lawns was possible only for the extremely wealthy estates and manor houses of the aristocracy. Labor-intensive methods of scything and shearing the grass were required to maintain the lawn in its correct state, and most of the land in England was required for more functional, agricultural purposes.[citation needed]

This all changed with the invention of the lawn mower by Edwin Beard Budding in 1830. Budding had the idea for a lawn mower after seeing a machine in a local cloth mill which used a cutting cylinder (or bladed reel) mounted on a bench to trim the irregular nap from the surface of woolen cloth and give a smooth finish.[19] Budding realised that a similar device could be used to cut grass if the mechanism was mounted in a wheeled frame to make the blades rotate close to the lawn's surface. His mower design was to be used primarily to cut the lawn on sports grounds and extensive gardens, as a superior alternative to the scythe, and he was granted a British patent on 31 August 1830.[20]

Budding went into partnership with a local engineer, John Ferrabee, who paid the costs of development and acquired rights to manufacture and sell lawn mowers and to license other manufacturers. Together they made mowers in a factory at Thrupp near Stroud.[21] Among the other companies manufacturing under license the most successful was Ransomes, Sims & Jefferies of Ipswich which began mower production as early as 1832.[22]

However, his model had two crucial drawbacks. It was immensely heavy (it was made of cast iron) and difficult to manoeuvre in the garden, and did not cut the grass very well. The blade would often spin above the grass uselessly.[22] It took ten more years and further innovations, including the advent of the Bessemer process for the production of the much lighter alloy steel and advances in motorization such as the drive chain, for the lawn mower to become a practical proposition. Middle-class families across the country, in imitation of aristocratic landscape gardens, began to grow finely trimmed lawns in their back gardens.[citation needed]

In the 1850s, Thomas Green of Leeds introduced a revolutionary mower design called the Silens Messor (meaning silent cutter), which used a chain to transmit power from the rear roller to the cutting cylinder. The machine was much lighter and quieter than the gear driven machines that preceded them, and won first prize at the first lawn mower trial at the London Horticultural Gardens.[22] Thus began a great expansion in the lawn mower production in the 1860s. James Sumner of Lancashire patented the first steam-powered lawn mower in 1893.[23] Around 1900, Ransomes' Automaton, available in chain- or gear-driven models, dominated the British market. In 1902, Ransomes produced the first commercially available mower powered by an internal combustion gasoline engine. JP Engineering of Leicester, founded after World War I, invented the first riding mowers.[citation needed]

This went hand-in-hand with a booming consumer market for lawns from the 1860s onward. With the increasing popularity of sports in the mid-Victorian period, the lawn mower was used to craft modern-style sporting ovals, playing fields, pitches and grass courts for the nascent sports of football, lawn bowls, lawn tennis and others.[24] The rise of Suburbanisation in the interwar period was heavily influenced by the garden city movement of Ebenezer Howard and the creation of the first garden suburbs at the turn of the 20th century.[25] The garden suburb, developed through the efforts of social reformer Henrietta Barnett and her husband, exemplified the incorporation of the well manicured lawn into suburban life.[26] Suburbs dramatically increased in size. Harrow Weald went from just 1,500 to over 10,000 while Pinner jumped from 3,00 to over 20,000. During the 1930s, over 4 million new suburban houses were built and the 'suburban revolution' had made England the most heavily suburbanized country in the world by a considerable margin.[27]

Lawns began to proliferate in America from the 1870s onwards. As more plants were introduced from Europe, lawns became smaller as they were filled with flower beds, perennials, sculptures, and water features.[28] Eventually the wealthy began to move away from the cities into new suburban communities. In 1856, an architectural book was published to accompany the development of the new suburbia that placed importance on the availability of a grassy space for children to play on and a space to grow fruits and vegetables that further imbued the lawn with cultural importance.[17] Lawns began making more appearances in development plans, magazine articles, and catalogs.[29] The lawn became less associated with being a status symbol, instead giving way to a landscape aesthetic. Improvements in the lawn mower and water supply enabled the spread of lawn culture from the Northeast to the South, where the grass grew more poorly.[17] This in combination with setback rules, which required all homes to have a 30-foot gap between the structure and the sidewalk meant that the lawn had found a specific place in suburbia.[28] In 1901, the United States Congress allotted $17,000 to the study of the best grasses for lawns, creating the spark for lawn care to become an industry.[30]

After World War II, a surplus of synthetic nitrogen in the United States led to chemical firms such as DuPont seeking to expand the market for fertilizers.[31] The suburban lawn offered an opportunity to market fertilizers, previously only used by farmers, to homeowners. In 1955, DuPont released Uramite, a slow-release nitrogen fertilizer specifically marketed for lawns. The trend continued throughout the 1960s, with chemical firms such as DuPont and Monsanto utilizing television advertising and other forms of advertisement to market pesticides, fertilizers, and herbicides.[32] The environmental impacts of this widespread chemical use were noticed as early as the 1960s, but suburban lawns as a source of pollution were largely ignored.[33]

Due to the harmful effects of excessive pesticide use, fertilizer use, climate change and pollution, a movement developed in the late 20th century to require organic lawn management. By the first decade of the 21st century, American homeowners were using ten times more pesticides per acre than farmers, poisoning an estimated 60 to 70 million birds yearly.[34] Lawn mowers are a significant contributor to pollution released into Earth's atmosphere, with a riding lawn mower producing the same amount of pollution in one hour of use as 34 cars.[34]

In recent years,[when?] some municipalities have banned synthetic pesticides and fertilizers and required organic land care techniques be used.[35] There are many locations with organic lawns that require organic landscaping.[citation needed]

Prior to European colonization, the grasses on the East Coast of North America were mostly broom straw, wild rye, and marsh grass. As Europeans moved into the region, it was noted by colonists in New England, more than others, that the grasses of the New World were inferior to those of England and that their livestock seemed to receive less nutrition from it. In fact, once livestock brought overseas from Europe spread throughout the colonies, much of the native grasses of New England disappeared, and an inventory list from the 17th century noted supplies of clover and grass seed from England. New colonists were even urged by their country and companies to bring grass seed with them to North America. By the late 17th century, a new market in imported grass seed had begun in New England.[17]

Much of the new grasses brought by Europeans spread quickly and effectively, often ahead of the colonists. One such species, Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon), became the most important pasture grass for the southern colonies.[citation needed]

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis) is a grass native to Europe or the Middle East. It was likely carried to Midwestern United States in the early 1600s by French missionaries and spread via the waterways to the region around Kentucky. However, it may also have spread across the Appalachian Mountains after an introduction on the east coast.[citation needed]

Farmers at first continued to harvest meadows and marshes composed of indigenous grasses until they became overgrazed. These areas quickly fell to erosion and were overrun with less favorable plant life. Soon, farmers began to purposefully plant new species of grass in these areas, hoping to improve the quality and quantity of hay to provide for their livestock as native species had a lower nutritive value. While Middle Eastern and Europeans species of grass did extremely well on the East Coast of North America, it was a number of grasses from the Mediterranean that dominated the Western seaboard. As cultivated grasses became valued for their nutritional benefits to livestock, farmers relied less and less on natural meadows in the more colonized areas of the country. Eventually even the grasses of the Great Plains were overrun with European species that were more durable to the grazing patterns of imported livestock.[17]

A pivotal factor in the spread of the lawn in America was the passage of legislation in 1938 of the 40-hour work week. Until then, Americans had typically worked half days on Saturdays, leaving little time to focus on their lawns. With this legislation and the housing boom following the Second World War, managed grass spaces became more commonplace.[28] The creation in the early 20th century of country clubs and golf courses completed the rise of lawn culture.[17]

According to study based on satellite observations by Cristina Milesi, NASA Earth System Science, its estimates: "More surface area in the United States is devoted to lawns than to individual irrigated crops such as corn or wheat.... area, covering about 128,000 square kilometers in all."[36]

Lawn monoculture was a reflection of more than an interest in offsetting depreciation, it propagated the homogeneity of the suburb itself. Although lawns had been a recognizable feature in English residences since the 19th century, a revolution in industrialization and monoculture of the lawn since the Second World War fundamentally changed the ecology of the lawn. Money and ideas flowed back from Europe after the U.S. entered WWI, changing the way Americans interacted with themselves and nature, and the industrialization of war hastened the industrialization of pest control.[37] Intensive suburbanization both concentrated and expanded the spread of lawn maintenance which meant increased inputs in not only petrochemicals, fertilizers, and pesticides, but also natural resources like water.[2][17][28]