Equipment used to transfer heat between fluids

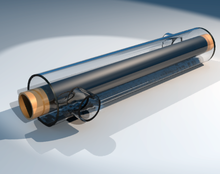

Tubular heat exchanger

Tubular heat exchanger

Partial view into inlet plenum of shell and tube heat exchanger of a refrigerant based chiller for providing air-conditioning to a building

Partial view into inlet plenum of shell and tube heat exchanger of a refrigerant based chiller for providing air-conditioning to a building

A heat exchanger is a system used to transfer heat between a source and a working fluid. Heat exchangers are used in both cooling and heating processes.[1] The fluids may be separated by a solid wall to prevent mixing or they may be in direct contact.[2] They are widely used in space heating, refrigeration, air conditioning, power stations, chemical plants, petrochemical plants, petroleum refineries, natural-gas processing, and sewage treatment. The classic example of a heat exchanger is found in an internal combustion engine in which a circulating fluid known as engine coolant flows through radiator coils and air flows past the coils, which cools the coolant and heats the incoming air. Another example is the heat sink, which is a passive heat exchanger that transfers the heat generated by an electronic or a mechanical device to a fluid medium, often air or a liquid coolant.[3]

Flow arrangement

[edit]

Countercurrent (A) and parallel (B) flows

Countercurrent (A) and parallel (B) flows

There are three primary classifications of heat exchangers according to their flow arrangement. In parallel-flow heat exchangers, the two fluids enter the exchanger at the same end, and travel in parallel to one another to the other side. In counter-flow heat exchangers the fluids enter the exchanger from opposite ends. The counter current design is the most efficient, in that it can transfer the most heat from the heat (transfer) medium per unit mass due to the fact that the average temperature difference along any unit length is higher. See countercurrent exchange. In a cross-flow heat exchanger, the fluids travel roughly perpendicular to one another through the exchanger.

-

Fig. 1: Shell and tube heat exchanger, single pass (1–1 parallel flow)

-

Fig. 2: Shell and tube heat exchanger, 2-pass tube side (1–2 crossflow)

-

Fig. 3: Shell and tube heat exchanger, 2-pass shell side, 2-pass tube side (2-2 countercurrent)

For efficiency, heat exchangers are designed to maximize the surface area of the wall between the two fluids, while minimizing resistance to fluid flow through the exchanger. The exchanger's performance can also be affected by the addition of fins or corrugations in one or both directions, which increase surface area and may channel fluid flow or induce turbulence.

The driving temperature across the heat transfer surface varies with position, but an appropriate mean temperature can be defined. In most simple systems this is the "log mean temperature difference" (LMTD). Sometimes direct knowledge of the LMTD is not available and the NTU method is used.

Types

[edit]

Double pipe heat exchangers are the simplest exchangers used in industries. On one hand, these heat exchangers are cheap for both design and maintenance, making them a good choice for small industries. On the other hand, their low efficiency coupled with the high space occupied in large scales, has led modern industries to use more efficient heat exchangers like shell and tube or plate. However, since double pipe heat exchangers are simple, they are used to teach heat exchanger design basics to students as the fundamental rules for all heat exchangers are the same.

1. Double-pipe heat exchanger

When one fluid flows through the smaller pipe, the other flows through the annular gap between the two pipes. These flows may be parallel or counter-flows in a double pipe heat exchanger.

(a) Parallel flow, where both hot and cold liquids enter the heat exchanger from the same side, flow in the same direction and exit at the same end. This configuration is preferable when the two fluids are intended to reach exactly the same temperature, as it reduces thermal stress and produces a more uniform rate of heat transfer.

(b) Counter-flow, where hot and cold fluids enter opposite sides of the heat exchanger, flow in opposite directions, and exit at opposite ends. This configuration is preferable when the objective is to maximize heat transfer between the fluids, as it creates a larger temperature differential when used under otherwise similar conditions.[citation needed]

The figure above illustrates the parallel and counter-flow flow directions of the fluid exchanger.

2. Shell-and-tube heat exchanger

In a shell-and-tube heat exchanger, two fluids at different temperatures flow through the heat exchanger. One of the fluids flows through the tube side and the other fluid flows outside the tubes, but inside the shell (shell side).

Baffles are used to support the tubes, direct the fluid flow to the tubes in an approximately natural manner, and maximize the turbulence of the shell fluid. There are many various kinds of baffles, and the choice of baffle form, spacing, and geometry depends on the allowable flow rate of the drop in shell-side force, the need for tube support, and the flow-induced vibrations. There are several variations of shell-and-tube exchangers available; the differences lie in the arrangement of flow configurations and details of construction.

In application to cool air with shell-and-tube technology (such as intercooler / charge air cooler for combustion engines), fins can be added on the tubes to increase heat transfer area on air side and create a tubes & fins configuration.

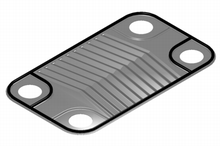

3. Plate Heat Exchanger

A plate heat exchanger contains an amount of thin shaped heat transfer plates bundled together. The gasket arrangement of each pair of plates provides two separate channel system. Each pair of plates form a channel where the fluid can flow through. The pairs are attached by welding and bolting methods. The following shows the components in the heat exchanger.

In single channels the configuration of the gaskets enables flow through. Thus, this allows the main and secondary media in counter-current flow. A gasket plate heat exchanger has a heat region from corrugated plates. The gasket function as seal between plates and they are located between frame and pressure plates. Fluid flows in a counter current direction throughout the heat exchanger. An efficient thermal performance is produced. Plates are produced in different depths, sizes and corrugated shapes. There are different types of plates available including plate and frame, plate and shell and spiral plate heat exchangers. The distribution area guarantees the flow of fluid to the whole heat transfer surface. This helps to prevent stagnant area that can cause accumulation of unwanted material on solid surfaces. High flow turbulence between plates results in a greater transfer of heat and a decrease in pressure.

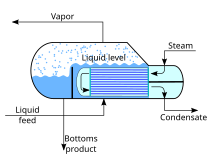

4. Condensers and Boilers Heat exchangers using a two-phase heat transfer system are condensers, boilers and evaporators. Condensers are instruments that take and cool hot gas or vapor to the point of condensation and transform the gas into a liquid form. The point at which liquid transforms to gas is called vaporization and vice versa is called condensation. Surface condenser is the most common type of condenser where it includes a water supply device. Figure 5 below displays a two-pass surface condenser.

The pressure of steam at the turbine outlet is low where the steam density is very low where the flow rate is very high. To prevent a decrease in pressure in the movement of steam from the turbine to condenser, the condenser unit is placed underneath and connected to the turbine. Inside the tubes the cooling water runs in a parallel way, while steam moves in a vertical downward position from the wide opening at the top and travel through the tube. Furthermore, boilers are categorized as initial application of heat exchangers. The word steam generator was regularly used to describe a boiler unit where a hot liquid stream is the source of heat rather than the combustion products. Depending on the dimensions and configurations the boilers are manufactured. Several boilers are only able to produce hot fluid while on the other hand the others are manufactured for steam production.

Shell and tube

[edit]

Main article: Shell and tube heat exchanger

A shell and tube heat exchanger

A shell and tube heat exchanger

Shell and tube heat exchanger

Shell and tube heat exchanger

Shell and tube heat exchangers consist of a series of tubes which contain fluid that must be either heated or cooled. A second fluid runs over the tubes that are being heated or cooled so that it can either provide the heat or absorb the heat required. A set of tubes is called the tube bundle and can be made up of several types of tubes: plain, longitudinally finned, etc. Shell and tube heat exchangers are typically used for high-pressure applications (with pressures greater than 30 bar and temperatures greater than 260 °C).[4] This is because the shell and tube heat exchangers are robust due to their shape.

Several thermal design features must be considered when designing the tubes in the shell and tube heat exchangers: There can be many variations on the shell and tube design. Typically, the ends of each tube are connected to plenums (sometimes called water boxes) through holes in tubesheets. The tubes may be straight or bent in the shape of a U, called U-tubes.

- Tube diameter: Using a small tube diameter makes the heat exchanger both economical and compact. However, it is more likely for the heat exchanger to foul up faster and the small size makes mechanical cleaning of the fouling difficult. To prevail over the fouling and cleaning problems, larger tube diameters can be used. Thus to determine the tube diameter, the available space, cost and fouling nature of the fluids must be considered.

- Tube thickness: The thickness of the wall of the tubes is usually determined to ensure:

- There is enough room for corrosion

- That flow-induced vibration has resistance

- Axial strength

- Availability of spare parts

- Hoop strength (to withstand internal tube pressure)

- Buckling strength (to withstand overpressure in the shell)

- Tube length: heat exchangers are usually cheaper when they have a smaller shell diameter and a long tube length. Thus, typically there is an aim to make the heat exchanger as long as physically possible whilst not exceeding production capabilities. However, there are many limitations for this, including space available at the installation site and the need to ensure tubes are available in lengths that are twice the required length (so they can be withdrawn and replaced). Also, long, thin tubes are difficult to take out and replace.

- Tube pitch: when designing the tubes, it is practical to ensure that the tube pitch (i.e., the centre-centre distance of adjoining tubes) is not less than 1.25 times the tubes' outside diameter. A larger tube pitch leads to a larger overall shell diameter, which leads to a more expensive heat exchanger.

- Tube corrugation: this type of tubes, mainly used for the inner tubes, increases the turbulence of the fluids and the effect is very important in the heat transfer giving a better performance.

- Tube Layout: refers to how tubes are positioned within the shell. There are four main types of tube layout, which are, triangular (30°), rotated triangular (60°), square (90°) and rotated square (45°). The triangular patterns are employed to give greater heat transfer as they force the fluid to flow in a more turbulent fashion around the piping. Square patterns are employed where high fouling is experienced and cleaning is more regular.

- Baffle Design: baffles are used in shell and tube heat exchangers to direct fluid across the tube bundle. They run perpendicularly to the shell and hold the bundle, preventing the tubes from sagging over a long length. They can also prevent the tubes from vibrating. The most common type of baffle is the segmental baffle. The semicircular segmental baffles are oriented at 180 degrees to the adjacent baffles forcing the fluid to flow upward and downwards between the tube bundle. Baffle spacing is of large thermodynamic concern when designing shell and tube heat exchangers. Baffles must be spaced with consideration for the conversion of pressure drop and heat transfer. For thermo economic optimization it is suggested that the baffles be spaced no closer than 20% of the shell's inner diameter. Having baffles spaced too closely causes a greater pressure drop because of flow redirection. Consequently, having the baffles spaced too far apart means that there may be cooler spots in the corners between baffles. It is also important to ensure the baffles are spaced close enough that the tubes do not sag. The other main type of baffle is the disc and doughnut baffle, which consists of two concentric baffles. An outer, wider baffle looks like a doughnut, whilst the inner baffle is shaped like a disk. This type of baffle forces the fluid to pass around each side of the disk then through the doughnut baffle generating a different type of fluid flow.

- Tubes & fins Design: in application to cool air with shell-and-tube technology (such as intercooler / charge air cooler for combustion engines), the difference in heat transfer between air and cold fluid can be such that there is a need to increase heat transfer area on air side. For this function fins can be added on the tubes to increase heat transfer area on air side and create a tubes & fins configuration.

Fixed tube liquid-cooled heat exchangers especially suitable for marine and harsh applications can be assembled with brass shells, copper tubes, brass baffles, and forged brass integral end hubs.[citation needed] (See: Copper in heat exchangers).

Plate

[edit]

Main article: Plate heat exchanger

Conceptual diagram of a plate and frame heat exchanger

Conceptual diagram of a plate and frame heat exchanger

A single plate heat exchanger

A single plate heat exchanger

An interchangeable plate heat exchanger directly applied to the system of a swimming pool

An interchangeable plate heat exchanger directly applied to the system of a swimming pool

Another type of heat exchanger is the plate heat exchanger. These exchangers are composed of many thin, slightly separated plates that have very large surface areas and small fluid flow passages for heat transfer. Advances in gasket and brazing technology have made the plate-type heat exchanger increasingly practical. In HVAC applications, large heat exchangers of this type are called plate-and-frame; when used in open loops, these heat exchangers are normally of the gasket type to allow periodic disassembly, cleaning, and inspection. There are many types of permanently bonded plate heat exchangers, such as dip-brazed, vacuum-brazed, and welded plate varieties, and they are often specified for closed-loop applications such as refrigeration. Plate heat exchangers also differ in the types of plates that are used, and in the configurations of those plates. Some plates may be stamped with "chevron", dimpled, or other patterns, where others may have machined fins and/or grooves.

When compared to shell and tube exchangers, the stacked-plate arrangement typically has lower volume and cost. Another difference between the two is that plate exchangers typically serve low to medium pressure fluids, compared to medium and high pressures of shell and tube. A third and important difference is that plate exchangers employ more countercurrent flow rather than cross current flow, which allows lower approach temperature differences, high temperature changes, and increased efficiencies.

Plate and shell

[edit]

A third type of heat exchanger is a plate and shell heat exchanger, which combines plate heat exchanger with shell and tube heat exchanger technologies. The heart of the heat exchanger contains a fully welded circular plate pack made by pressing and cutting round plates and welding them together. Nozzles carry flow in and out of the platepack (the 'Plate side' flowpath). The fully welded platepack is assembled into an outer shell that creates a second flowpath ( the 'Shell side'). Plate and shell technology offers high heat transfer, high pressure, high operating temperature, compact size, low fouling and close approach temperature. In particular, it does completely without gaskets, which provides security against leakage at high pressures and temperatures.

Adiabatic wheel

[edit]

A fourth type of heat exchanger uses an intermediate fluid or solid store to hold heat, which is then moved to the other side of the heat exchanger to be released. Two examples of this are adiabatic wheels, which consist of a large wheel with fine threads rotating through the hot and cold fluids, and fluid heat exchangers.

Plate fin

[edit]

Main article: Plate fin heat exchanger

This type of heat exchanger uses "sandwiched" passages containing fins to increase the effectiveness of the unit. The designs include crossflow and counterflow coupled with various fin configurations such as straight fins, offset fins and wavy fins.

Plate and fin heat exchangers are usually made of aluminum alloys, which provide high heat transfer efficiency. The material enables the system to operate at a lower temperature difference and reduce the weight of the equipment. Plate and fin heat exchangers are mostly used for low temperature services such as natural gas, helium and oxygen liquefaction plants, air separation plants and transport industries such as motor and aircraft engines.

Advantages of plate and fin heat exchangers:

- High heat transfer efficiency especially in gas treatment

- Larger heat transfer area

- Approximately 5 times lighter in weight than that of shell and tube heat exchanger. [citation needed]

- Able to withstand high pressure

Disadvantages of plate and fin heat exchangers:

- Might cause clogging as the pathways are very narrow

- Difficult to clean the pathways

- Aluminium alloys are susceptible to Mercury Liquid Embrittlement Failure

Finned tube

[edit]

The usage of fins in a tube-based heat exchanger is common when one of the working fluids is a low-pressure gas, and is typical for heat exchangers that operate using ambient air, such as automotive radiators and HVAC air condensers. Fins dramatically increase the surface area with which heat can be exchanged, which improves the efficiency of conducting heat to a fluid with very low thermal conductivity, such as air. The fins are typically made from aluminium or copper since they must conduct heat from the tube along the length of the fins, which are usually very thin.

The main construction types of finned tube exchangers are:

- A stack of evenly-spaced metal plates act as the fins and the tubes are pressed through pre-cut holes in the fins, good thermal contact usually being achieved by deformation of the fins around the tube. This is typical construction for HVAC air coils and large refrigeration condensers.

- Fins are spiral-wound onto individual tubes as a continuous strip, the tubes can then be assembled in banks, bent in a serpentine pattern, or wound into large spirals.

- Zig-zag metal strips are sandwiched between flat rectangular tubes, often being soldered or brazed together for good thermal and mechanical strength. This is common in low-pressure heat exchangers such as water-cooling radiators. Regular flat tubes will expand and deform if exposed to high pressures but flat microchannel tubes allow this construction to be used for high pressures.[5]

Stacked-fin or spiral-wound construction can be used for the tubes inside shell-and-tube heat exchangers when high efficiency thermal transfer to a gas is required.

In electronics cooling, heat sinks, particularly those using heat pipes, can have a stacked-fin construction.

Pillow plate

[edit]

A pillow plate heat exchanger is commonly used in the dairy industry for cooling milk in large direct-expansion stainless steel bulk tanks. Nearly the entire surface area of a tank can be integrated with this heat exchanger, without gaps that would occur between pipes welded to the exterior of the tank. Pillow plates can also be constructed as flat plates that are stacked inside a tank. The relatively flat surface of the plates allows easy cleaning, especially in sterile applications.

The pillow plate can be constructed using either a thin sheet of metal welded to the thicker surface of a tank or vessel, or two thin sheets welded together. The surface of the plate is welded with a regular pattern of dots or a serpentine pattern of weld lines. After welding the enclosed space is pressurised with sufficient force to cause the thin metal to bulge out around the welds, providing a space for heat exchanger liquids to flow, and creating a characteristic appearance of a swelled pillow formed out of metal.

Waste heat recovery units

[edit]

|

|

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

A waste heat recovery unit (WHRU) is a heat exchanger that recovers heat from a hot gas stream while transferring it to a working medium, typically water or oils. The hot gas stream can be the exhaust gas from a gas turbine or a diesel engine or a waste gas from industry or refinery.

Large systems with high volume and temperature gas streams, typical in industry, can benefit from steam Rankine cycle (SRC) in a waste heat recovery unit, but these cycles are too expensive for small systems. The recovery of heat from low temperature systems requires different working fluids than steam.

An organic Rankine cycle (ORC) waste heat recovery unit can be more efficient at low temperature range using refrigerants that boil at lower temperatures than water. Typical organic refrigerants are ammonia, pentafluoropropane (R-245fa and R-245ca), and toluene.

The refrigerant is boiled by the heat source in the evaporator to produce super-heated vapor. This fluid is expanded in the turbine to convert thermal energy to kinetic energy, that is converted to electricity in the electrical generator. This energy transfer process decreases the temperature of the refrigerant that, in turn, condenses. The cycle is closed and completed using a pump to send the fluid back to the evaporator.

Dynamic scraped surface

[edit]

Another type of heat exchanger is called "(dynamic) scraped surface heat exchanger". This is mainly used for heating or cooling with high-viscosity products, crystallization processes, evaporation and high-fouling applications. Long running times are achieved due to the continuous scraping of the surface, thus avoiding fouling and achieving a sustainable heat transfer rate during the process.

Phase-change

[edit]

Typical kettle reboiler used for industrial distillation towers

Typical kettle reboiler used for industrial distillation towers

Typical water-cooled surface condenser

Typical water-cooled surface condenser

In addition to heating up or cooling down fluids in just a single phase, heat exchangers can be used either to heat a liquid to evaporate (or boil) it or used as condensers to cool a vapor and condense it to a liquid. In chemical plants and refineries, reboilers used to heat incoming feed for distillation towers are often heat exchangers.[6][7]

Distillation set-ups typically use condensers to condense distillate vapors back into liquid.

Power plants that use steam-driven turbines commonly use heat exchangers to boil water into steam. Heat exchangers or similar units for producing steam from water are often called boilers or steam generators.

In the nuclear power plants called pressurized water reactors, special large heat exchangers pass heat from the primary (reactor plant) system to the secondary (steam plant) system, producing steam from water in the process. These are called steam generators. All fossil-fueled and nuclear power plants using steam-driven turbines have surface condensers to convert the exhaust steam from the turbines into condensate (water) for re-use.[8][9]

To conserve energy and cooling capacity in chemical and other plants, regenerative heat exchangers can transfer heat from a stream that must be cooled to another stream that must be heated, such as distillate cooling and reboiler feed pre-heating.

This term can also refer to heat exchangers that contain a material within their structure that has a change of phase. This is usually a solid to liquid phase due to the small volume difference between these states. This change of phase effectively acts as a buffer because it occurs at a constant temperature but still allows for the heat exchanger to accept additional heat. One example where this has been investigated is for use in high power aircraft electronics.

Heat exchangers functioning in multiphase flow regimes may be subject to the Ledinegg instability.

[edit]

Direct contact heat exchangers involve heat transfer between hot and cold streams of two phases in the absence of a separating wall.[10] Thus such heat exchangers can be classified as:

- Gas – liquid

- Immiscible liquid – liquid

- Solid-liquid or solid – gas

Most direct contact heat exchangers fall under the Gas – Liquid category, where heat is transferred between a gas and liquid in the form of drops, films or sprays.[4]

Such types of heat exchangers are used predominantly in air conditioning, humidification, industrial hot water heating, water cooling and condensing plants.[11]

| Phases[12] |

Continuous phase |

Driving force |

Change of phase |

Examples |

| Gas – Liquid |

Gas |

Gravity |

No |

Spray columns, packed columns |

| |

|

|

Yes |

Cooling towers, falling droplet evaporators |

| |

|

Forced |

No |

Spray coolers/quenchers |

| |

|

Liquid flow |

Yes |

Spray condensers/evaporation, jet condensers |

| |

Liquid |

Gravity |

No |

Bubble columns, perforated tray columns |

| |

|

|

Yes |

Bubble column condensers |

| |

|

Forced |

No |

Gas spargers |

| |

|

Gas flow |

Yes |

Direct contact evaporators, submerged combustion |

Microchannel

[edit]

Microchannel heat exchangers are multi-pass parallel flow heat exchangers consisting of three main elements: manifolds (inlet and outlet), multi-port tubes with the hydraulic diameters smaller than 1mm, and fins. All the elements usually brazed together using controllable atmosphere brazing process. Microchannel heat exchangers are characterized by high heat transfer ratio, low refrigerant charges, compact size, and lower airside pressure drops compared to finned tube heat exchangers.[citation needed] Microchannel heat exchangers are widely used in automotive industry as the car radiators, and as condenser, evaporator, and cooling/heating coils in HVAC industry.

Main article: Micro heat exchanger

Micro heat exchangers, Micro-scale heat exchangers, or microstructured heat exchangers are heat exchangers in which (at least one) fluid flows in lateral confinements with typical dimensions below 1 mm. The most typical such confinement are microchannels, which are channels with a hydraulic diameter below 1 mm. Microchannel heat exchangers can be made from metal or ceramics.[13] Microchannel heat exchangers can be used for many applications including:

- high-performance aircraft gas turbine engines[14]

- heat pumps[15]

- Microprocessor and microchip cooling[16]

- air conditioning[17]

HVAC and refrigeration air coils

[edit]

One of the widest uses of heat exchangers is for refrigeration and air conditioning. This class of heat exchangers is commonly called air coils, or just coils due to their often-serpentine internal tubing, or condensers in the case of refrigeration, and are typically of the finned tube type. Liquid-to-air, or air-to-liquid HVAC coils are typically of modified crossflow arrangement. In vehicles, heat coils are often called heater cores.

On the liquid side of these heat exchangers, the common fluids are water, a water-glycol solution, steam, or a refrigerant. For heating coils, hot water and steam are the most common, and this heated fluid is supplied by boilers, for example. For cooling coils, chilled water and refrigerant are most common. Chilled water is supplied from a chiller that is potentially located very far away, but refrigerant must come from a nearby condensing unit. When a refrigerant is used, the cooling coil is the evaporator, and the heating coil is the condenser in the vapor-compression refrigeration cycle. HVAC coils that use this direct-expansion of refrigerants are commonly called DX coils. Some DX coils are "microchannel" type.[5]

On the air side of HVAC coils a significant difference exists between those used for heating, and those for cooling. Due to psychrometrics, air that is cooled often has moisture condensing out of it, except with extremely dry air flows. Heating some air increases that airflow's capacity to hold water. So heating coils need not consider moisture condensation on their air-side, but cooling coils must be adequately designed and selected to handle their particular latent (moisture) as well as the sensible (cooling) loads. The water that is removed is called condensate.

For many climates, water or steam HVAC coils can be exposed to freezing conditions. Because water expands upon freezing, these somewhat expensive and difficult to replace thin-walled heat exchangers can easily be damaged or destroyed by just one freeze. As such, freeze protection of coils is a major concern of HVAC designers, installers, and operators.

The introduction of indentations placed within the heat exchange fins controlled condensation, allowing water molecules to remain in the cooled air.[18]

The heat exchangers in direct-combustion furnaces, typical in many residences, are not 'coils'. They are, instead, gas-to-air heat exchangers that are typically made of stamped steel sheet metal. The combustion products pass on one side of these heat exchangers, and air to heat on the other. A cracked heat exchanger is therefore a dangerous situation that requires immediate attention because combustion products may enter living space.

Helical-coil

[edit]

Helical-Coil Heat Exchanger sketch, which consists of a shell, core, and tubes (Scott S. Haraburda design)

Helical-Coil Heat Exchanger sketch, which consists of a shell, core, and tubes (Scott S. Haraburda design)

Although double-pipe heat exchangers are the simplest to design, the better choice in the following cases would be the helical-coil heat exchanger (HCHE):

- The main advantage of the HCHE, like that for the Spiral heat exchanger (SHE), is its highly efficient use of space, especially when it's limited and not enough straight pipe can be laid.[19]

- Under conditions of low flowrates (or laminar flow), such that the typical shell-and-tube exchangers have low heat-transfer coefficients and becoming uneconomical.[19]

- When there is low pressure in one of the fluids, usually from accumulated pressure drops in other process equipment.[19]

- When one of the fluids has components in multiple phases (solids, liquids, and gases), which tends to create mechanical problems during operations, such as plugging of small-diameter tubes.[20] Cleaning of helical coils for these multiple-phase fluids can prove to be more difficult than its shell and tube counterpart; however the helical coil unit would require cleaning less often.

These have been used in the nuclear industry as a method for exchanging heat in a sodium system for large liquid metal fast breeder reactors since the early 1970s, using an HCHE device invented by Charles E. Boardman and John H. Germer.[21] There are several simple methods for designing HCHE for all types of manufacturing industries, such as using the Ramachandra K. Patil (et al.) method from India and the Scott S. Haraburda method from the United States.[19][20]

However, these are based upon assumptions of estimating inside heat transfer coefficient, predicting flow around the outside of the coil, and upon constant heat flux.[22]

Spiral

[edit]

Schematic drawing of a spiral heat exchanger

Schematic drawing of a spiral heat exchanger

A modification to the perpendicular flow of the typical HCHE involves the replacement of shell with another coiled tube, allowing the two fluids to flow parallel to one another, and which requires the use of different design calculations.[23] These are the Spiral Heat Exchangers (SHE), which may refer to a helical (coiled) tube configuration, more generally, the term refers to a pair of flat surfaces that are coiled to form the two channels in a counter-flow arrangement. Each of the two channels has one long curved path. A pair of fluid ports are connected tangentially to the outer arms of the spiral, and axial ports are common, but optional.[24]

The main advantage of the SHE is its highly efficient use of space. This attribute is often leveraged and partially reallocated to gain other improvements in performance, according to well known tradeoffs in heat exchanger design. (A notable tradeoff is capital cost vs operating cost.) A compact SHE may be used to have a smaller footprint and thus lower all-around capital costs, or an oversized SHE may be used to have less pressure drop, less pumping energy, higher thermal efficiency, and lower energy costs.

Construction

[edit]

The distance between the sheets in the spiral channels is maintained by using spacer studs that were welded prior to rolling. Once the main spiral pack has been rolled, alternate top and bottom edges are welded and each end closed by a gasketed flat or conical cover bolted to the body. This ensures no mixing of the two fluids occurs. Any leakage is from the periphery cover to the atmosphere, or to a passage that contains the same fluid.[25]

Self cleaning

[edit]

Spiral heat exchangers are often used in the heating of fluids that contain solids and thus tend to foul the inside of the heat exchanger. The low pressure drop lets the SHE handle fouling more easily. The SHE uses a “self cleaning” mechanism, whereby fouled surfaces cause a localized increase in fluid velocity, thus increasing the drag (or fluid friction) on the fouled surface, thus helping to dislodge the blockage and keep the heat exchanger clean. "The internal walls that make up the heat transfer surface are often rather thick, which makes the SHE very robust, and able to last a long time in demanding environments."[citation needed] They are also easily cleaned, opening out like an oven where any buildup of foulant can be removed by pressure washing.

Self-cleaning water filters are used to keep the system clean and running without the need to shut down or replace cartridges and bags.

Flow arrangements

[edit]

A comparison between the operations and effects of a cocurrent and a countercurrent flow exchange system is depicted by the upper and lower diagrams respectively. In both it is assumed (and indicated) that red has a higher value (e.g. of temperature) than blue and that the property being transported in the channels therefore flows from red to blue. Channels are contiguous if effective exchange is to occur (i.e. there can be no gap between the channels).

A comparison between the operations and effects of a cocurrent and a countercurrent flow exchange system is depicted by the upper and lower diagrams respectively. In both it is assumed (and indicated) that red has a higher value (e.g. of temperature) than blue and that the property being transported in the channels therefore flows from red to blue. Channels are contiguous if effective exchange is to occur (i.e. there can be no gap between the channels).

There are three main types of flows in a spiral heat exchanger:

- Counter-current Flow: Fluids flow in opposite directions. These are used for liquid-liquid, condensing and gas cooling applications. Units are usually mounted vertically when condensing vapour and mounted horizontally when handling high concentrations of solids.

- Spiral Flow/Cross Flow: One fluid is in spiral flow and the other in a cross flow. Spiral flow passages are welded at each side for this type of spiral heat exchanger. This type of flow is suitable for handling low density gas, which passes through the cross flow, avoiding pressure loss. It can be used for liquid-liquid applications if one liquid has a considerably greater flow rate than the other.

- Distributed Vapour/Spiral flow: This design is that of a condenser, and is usually mounted vertically. It is designed to cater for the sub-cooling of both condensate and non-condensables. The coolant moves in a spiral and leaves via the top. Hot gases that enter leave as condensate via the bottom outlet.

Applications

[edit]

The Spiral heat exchanger is good for applications such as pasteurization, digester heating, heat recovery, pre-heating (see: recuperator), and effluent cooling. For sludge treatment, SHEs are generally smaller than other types of heat exchangers.[citation needed] These are used to transfer the heat.

Selection

[edit]

Due to the many variables involved, selecting optimal heat exchangers is challenging. Hand calculations are possible, but many iterations are typically needed. As such, heat exchangers are most often selected via computer programs, either by system designers, who are typically engineers, or by equipment vendors.

To select an appropriate heat exchanger, the system designers (or equipment vendors) would firstly consider the design limitations for each heat exchanger type. Though cost is often the primary criterion, several other selection criteria are important:

- High/low pressure limits

- Thermal performance

- Temperature ranges

- Product mix (liquid/liquid, particulates or high-solids liquid)

- Pressure drops across the exchanger

- Fluid flow capacity

- Cleanability, maintenance and repair

- Materials required for construction

- Ability and ease of future expansion

- Material selection, such as copper, aluminium, carbon steel, stainless steel, nickel alloys, ceramic, polymer, and titanium.[26][27]

Small-diameter coil technologies are becoming more popular in modern air conditioning and refrigeration systems because they have better rates of heat transfer than conventional sized condenser and evaporator coils with round copper tubes and aluminum or copper fin that have been the standard in the HVAC industry. Small diameter coils can withstand the higher pressures required by the new generation of environmentally friendlier refrigerants. Two small diameter coil technologies are currently available for air conditioning and refrigeration products: copper microgroove[28] and brazed aluminum microchannel.[citation needed]

Choosing the right heat exchanger (HX) requires some knowledge of the different heat exchanger types, as well as the environment where the unit must operate. Typically in the manufacturing industry, several differing types of heat exchangers are used for just one process or system to derive the final product. For example, a kettle HX for pre-heating, a double pipe HX for the 'carrier' fluid and a plate and frame HX for final cooling. With sufficient knowledge of heat exchanger types and operating requirements, an appropriate selection can be made to optimise the process.[29]

Monitoring and maintenance

[edit]

Online monitoring of commercial heat exchangers is done by tracking the overall heat transfer coefficient. The overall heat transfer coefficient tends to decline over time due to fouling.

By periodically calculating the overall heat transfer coefficient from exchanger flow rates and temperatures, the owner of the heat exchanger can estimate when cleaning the heat exchanger is economically attractive.

Integrity inspection of plate and tubular heat exchanger can be tested in situ by the conductivity or helium gas methods. These methods confirm the integrity of the plates or tubes to prevent any cross contamination and the condition of the gaskets.

Mechanical integrity monitoring of heat exchanger tubes may be conducted through Nondestructive methods such as eddy current testing.

Fouling

[edit]

Main article: Fouling

A heat exchanger in a steam power station contaminated with macrofouling

A heat exchanger in a steam power station contaminated with macrofouling

Fouling occurs when impurities deposit on the heat exchange surface. Deposition of these impurities can decrease heat transfer effectiveness significantly over time and are caused by:

- Low wall shear stress

- Low fluid velocities

- High fluid velocities

- Reaction product solid precipitation

- Precipitation of dissolved impurities due to elevated wall temperatures

The rate of heat exchanger fouling is determined by the rate of particle deposition less re-entrainment/suppression. This model was originally proposed in 1959 by Kern and Seaton.

Crude Oil Exchanger Fouling. In commercial crude oil refining, crude oil is heated from 21 °C (70 °F) to 343 °C (649 °F) prior to entering the distillation column. A series of shell and tube heat exchangers typically exchange heat between crude oil and other oil streams to heat the crude to 260 °C (500 °F) prior to heating in a furnace. Fouling occurs on the crude side of these exchangers due to asphaltene insolubility. The nature of asphaltene solubility in crude oil was successfully modeled by Wiehe and Kennedy.[30] The precipitation of insoluble asphaltenes in crude preheat trains has been successfully modeled as a first order reaction by Ebert and Panchal[31] who expanded on the work of Kern and Seaton.

Cooling Water Fouling. Cooling water systems are susceptible to fouling. Cooling water typically has a high total dissolved solids content and suspended colloidal solids. Localized precipitation of dissolved solids occurs at the heat exchange surface due to wall temperatures higher than bulk fluid temperature. Low fluid velocities (less than 3 ft/s) allow suspended solids to settle on the heat exchange surface. Cooling water is typically on the tube side of a shell and tube exchanger because it's easy to clean. To prevent fouling, designers typically ensure that cooling water velocity is greater than 0.9 m/s and bulk fluid temperature is maintained less than 60 °C (140 °F). Other approaches to control fouling control combine the "blind" application of biocides and anti-scale chemicals with periodic lab testing.

Maintenance

[edit]

Plate and frame heat exchangers can be disassembled and cleaned periodically. Tubular heat exchangers can be cleaned by such methods as acid cleaning, sandblasting, high-pressure water jet, bullet cleaning, or drill rods.

In large-scale cooling water systems for heat exchangers, water treatment such as purification, addition of chemicals, and testing, is used to minimize fouling of the heat exchange equipment. Other water treatment is also used in steam systems for power plants, etc. to minimize fouling and corrosion of the heat exchange and other equipment.

A variety of companies have started using water borne oscillations technology to prevent biofouling. Without the use of chemicals, this type of technology has helped in providing a low-pressure drop in heat exchangers.

Design and manufacturing regulations

[edit]

The design and manufacturing of heat exchangers has numerous regulations, which vary according to the region in which they will be used.

Design and manufacturing codes include: ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code (US); PD 5500 (UK); BS 1566 (UK);[32] EN 13445 (EU); CODAP (French); Pressure Equipment Safety Regulations 2016 (PER) (UK); Pressure Equipment Directive (EU); NORSOK (Norwegian); TEMA;[33] API 12; and API 560.[citation needed]

In nature

[edit]

Humans

[edit]

The human nasal passages serve as a heat exchanger, with cool air being inhaled and warm air being exhaled. Its effectiveness can be demonstrated by putting the hand in front of the face and exhaling, first through the nose and then through the mouth. Air exhaled through the nose is substantially cooler.[34][35] This effect can be enhanced with clothing, by, for example, wearing a scarf over the face while breathing in cold weather.

In species that have external testes (such as human), the artery to the testis is surrounded by a mesh of veins called the pampiniform plexus. This cools the blood heading to the testes, while reheating the returning blood.

Birds, fish, marine mammals

[edit]

Counter-current exchange conservation circuit

Counter-current exchange conservation circuit

Further information: Counter-current exchange in biological systems

"Countercurrent" heat exchangers occur naturally in the circulatory systems of fish, whales and other marine mammals. Arteries to the skin carrying warm blood are intertwined with veins from the skin carrying cold blood, causing the warm arterial blood to exchange heat with the cold venous blood. This reduces the overall heat loss in cold water. Heat exchangers are also present in the tongues of baleen whales as large volumes of water flow through their mouths.[36][37] Wading birds use a similar system to limit heat losses from their body through their legs into the water.

Carotid rete

[edit]

Carotid rete is a counter-current heat exchanging organ in some ungulates. The blood ascending the carotid arteries on its way to the brain, flows via a network of vessels where heat is discharged to the veins of cooler blood descending from the nasal passages. The carotid rete allows Thomson's gazelle to maintain its brain almost 3 °C (5.4 °F) cooler than the rest of the body, and therefore aids in tolerating bursts in metabolic heat production such as associated with outrunning cheetahs (during which the body temperature exceeds the maximum temperature at which the brain could function).[38] Humans with other primates lack a carotid rete.[39]

In industry

[edit]

Heat exchangers are widely used in industry both for cooling and heating large scale industrial processes. The type and size of heat exchanger used can be tailored to suit a process depending on the type of fluid, its phase, temperature, density, viscosity, pressures, chemical composition and various other thermodynamic properties.

In many industrial processes there is waste of energy or a heat stream that is being exhausted, heat exchangers can be used to recover this heat and put it to use by heating a different stream in the process. This practice saves a lot of money in industry, as the heat supplied to other streams from the heat exchangers would otherwise come from an external source that is more expensive and more harmful to the environment.

Heat exchangers are used in many industries, including:

- Waste water treatment

- Refrigeration

- Wine and beer making

- Petroleum refining

- Nuclear power

In waste water treatment, heat exchangers play a vital role in maintaining optimal temperatures within anaerobic digesters to promote the growth of microbes that remove pollutants. Common types of heat exchangers used in this application are the double pipe heat exchanger as well as the plate and frame heat exchanger.

In aircraft

[edit]

In commercial aircraft heat exchangers are used to take heat from the engine's oil system to heat cold fuel.[40] This improves fuel efficiency, as well as reduces the possibility of water entrapped in the fuel freezing in components.[41]

Current market and forecast

[edit]

Estimated at US$17.5 billion in 2021, the global demand of heat exchangers is expected to experience robust growth of about 5% annually over the next years. The market value is expected to reach US$27 billion by 2030. With an expanding desire for environmentally friendly options and increased development of offices, retail sectors, and public buildings, market expansion is due to grow.[42]

A model of a simple heat exchanger

[edit]

A simple heat exchange [43][44] might be thought of as two straight pipes with fluid flow, which are thermally connected. Let the pipes be of equal length L, carrying fluids with heat capacity  (energy per unit mass per unit change in temperature) and let the mass flow rate of the fluids through the pipes, both in the same direction, be

(energy per unit mass per unit change in temperature) and let the mass flow rate of the fluids through the pipes, both in the same direction, be  (mass per unit time), where the subscript i applies to pipe 1 or pipe 2.

(mass per unit time), where the subscript i applies to pipe 1 or pipe 2.

Temperature profiles for the pipes are  and

and  where x is the distance along the pipe. Assume a steady state, so that the temperature profiles are not functions of time. Assume also that the only transfer of heat from a small volume of fluid in one pipe is to the fluid element in the other pipe at the same position, i.e., there is no transfer of heat along a pipe due to temperature differences in that pipe. By Newton's law of cooling the rate of change in energy of a small volume of fluid is proportional to the difference in temperatures between it and the corresponding element in the other pipe:

where x is the distance along the pipe. Assume a steady state, so that the temperature profiles are not functions of time. Assume also that the only transfer of heat from a small volume of fluid in one pipe is to the fluid element in the other pipe at the same position, i.e., there is no transfer of heat along a pipe due to temperature differences in that pipe. By Newton's law of cooling the rate of change in energy of a small volume of fluid is proportional to the difference in temperatures between it and the corresponding element in the other pipe:

( this is for parallel flow in the same direction and opposite temperature gradients, but for counter-flow heat exchange countercurrent exchange the sign is opposite in the second equation in front of  ), where

), where  is the thermal energy per unit length and γ is the thermal connection constant per unit length between the two pipes. This change in internal energy results in a change in the temperature of the fluid element. The time rate of change for the fluid element being carried along by the flow is:

is the thermal energy per unit length and γ is the thermal connection constant per unit length between the two pipes. This change in internal energy results in a change in the temperature of the fluid element. The time rate of change for the fluid element being carried along by the flow is:

where  is the "thermal mass flow rate". The differential equations governing the heat exchanger may now be written as:

is the "thermal mass flow rate". The differential equations governing the heat exchanger may now be written as:

Since the system is in a steady state, there are no partial derivatives of temperature with respect to time, and since there is no heat transfer along the pipe, there are no second derivatives in x as is found in the heat equation. These two coupled first-order differential equations may be solved to yield:

where  ,

,  ,

,

(this is for parallel-flow, but for counter-flow the sign in front of  is negative, so that if

is negative, so that if  , for the same "thermal mass flow rate" in both opposite directions, the gradient of temperature is constant and the temperatures linear in position x with a constant difference

, for the same "thermal mass flow rate" in both opposite directions, the gradient of temperature is constant and the temperatures linear in position x with a constant difference  along the exchanger, explaining why the counter current design countercurrent exchange is the most efficient )

along the exchanger, explaining why the counter current design countercurrent exchange is the most efficient )

and A and B are two as yet undetermined constants of integration. Let  and

and  be the temperatures at x=0 and let

be the temperatures at x=0 and let  and

and  be the temperatures at the end of the pipe at x=L. Define the average temperatures in each pipe as:

be the temperatures at the end of the pipe at x=L. Define the average temperatures in each pipe as:

Using the solutions above, these temperatures are:

-

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

Choosing any two of the temperatures above eliminates the constants of integration, letting us find the other four temperatures. We find the total energy transferred by integrating the expressions for the time rate of change of internal energy per unit length:

By the conservation of energy, the sum of the two energies is zero. The quantity  is known as the Log mean temperature difference, and is a measure of the effectiveness of the heat exchanger in transferring heat energy.

is known as the Log mean temperature difference, and is a measure of the effectiveness of the heat exchanger in transferring heat energy.

See also

[edit]

- Architectural engineering

- Chemical engineering

- Cooling tower

- Copper in heat exchangers

- Heat pipe

- Heat pump

- Heat recovery ventilation

- Jacketed vessel

- Log mean temperature difference (LMTD)

- Marine heat exchangers

- Mechanical engineering

- Micro heat exchanger

- Moving bed heat exchanger

- Packed bed and in particular Packed columns

- Pumpable ice technology

- Reboiler

- Recuperator, or cross plate heat exchanger

- Regenerator

- Run around coil

- Steam generator (nuclear power)

- Surface condenser

- Toroidal expansion joint

- Thermosiphon

- Thermal wheel, or rotary heat exchanger (including enthalpy wheel and desiccant wheel)

- Tube tool

- Waste heat

References

[edit]

- ^

Al-Sammarraie, Ahmed T.; Vafai, Kambiz (2017). "Heat transfer augmentation through convergence angles in a pipe". Numerical Heat Transfer, Part A: Applications. 72 (3): 197–214. Bibcode:2017NHTA...72..197A. doi:10.1080/10407782.2017.1372670. S2CID 125509773.

- ^ Sadik Kakaç; Hongtan Liu (2002). Heat Exchangers: Selection, Rating and Thermal Design (2nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0902-1.

- ^ Farzaneh, Mahsa; Forouzandeh, Azadeh; Al-Sammarraie, Ahmed T.; Salimpour, Mohammad Reza (2019). "Constructal Design of Circular Multilayer Microchannel Heat Sinks". Journal of Thermal Science and Engineering Applications. 11. doi:10.1115/1.4041196. S2CID 126162513.

- ^ a b Saunders, E. A. (1988). Heat Exchanges: Selection, Design and Construction. New York: Longman Scientific and Technical.

- ^ a b "MICROCHANNEL TECHNOLOGY" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 4, 2013.

- ^ Kister, Henry Z. (1992). Distillation Design (1st ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-034909-4.

- ^ Perry, Robert H.; Green, Don W. (1984). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-049479-4.

- ^ Air Pollution Control Orientation Course from website of the Air Pollution Training Institute

- ^ Energy savings in steam systems Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Figure 3a, Layout of surface condenser (scroll to page 11 of 34 PDF pages)

- ^ Coulson, J. & Richardson, J. (1983), Chemical Engineering – Design (SI Units), Volume 6, Pergamon Press, Oxford.

- ^ Hewitt G, Shires G, Bott T (1994), Process Heat Transfer, CRC Press Inc, Florida.

- ^ Table: Various Types of Gas – Liquid Direct Contact Heat Exchangers (Hewitt G, Shires G & Bott T, 1994)

- ^ Kee Robert J.; et al. (2011). "The design, fabrication, and evaluation of a ceramic counter-flow microchannel heat exchanger". Applied Thermal Engineering. 31 (11): 2004–2012. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2011.03.009.

- ^ Northcutt B.; Mudawar I. (2012). "Enhanced design of cross-flow microchannel heat exchanger module for high-performance aircraft gas turbine engines". Journal of Heat Transfer. 134 (6): 061801. doi:10.1115/1.4006037.

- ^ Moallem E.; Padhmanabhan S.; Cremaschi L.; Fisher D. E. (2012). "Experimental investigation of the surface temperature and water retention effects on the frosting performance of a compact microchannel heat exchanger for heat pump systems". International Journal of Refrigeration. 35 (1): 171–186. doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2011.08.010.

- ^ Sarvar-Ardeh, S., Rafee, R., Rashidi, S. (2021). Hybrid nanofluids with temperature-dependent properties for use in double-layered microchannel heat sink; hydrothermal investigation. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers. cite journal https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2021.05.007

- ^ Xu, B., Shi, J., Wang, Y., Chen, J., Li, F., & Li, D. (2014). Experimental Study of Fouling Performance of Air Conditioning System with Microchannel Heat Exchanger.

- ^ Patent 2,046,968 John C Raisley[dead link] issued July 7, 1936; filed Jan. 8, 1934 [1]

- ^ a b c d Patil, Ramachandra K.; Shende, B.W.; Ghosh, Prasanfa K. (13 December 1982). "Designing a helical-coil heat exchanger". Chemical Engineering. 92 (24): 85–88. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ a b Haraburda, Scott S. (July 1995). "Three-Phase Flow? Consider Helical-Coil Heat Exchanger". Chemical Engineering. 102 (7): 149–151. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^

US 3805890, Boardman, Charles E. & Germer, John H., "Helical Coil Heat Exchanger", issued 1974

- ^ Rennie, Timothy J. (2004). Numerical And Experimental Studies Of A Doublepipe Helical Heat Exchanger (PDF) (Ph.D.). Montreal: McGill University. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ Rennie, Timothy J.; Raghavan, Vijaya G.S. (September 2005). "Experimental studies of a double-pipe helical heat exchanger". Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science. 29 (8): 919–924. doi:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2005.02.001.

- ^ "Cooling Text". Archived from the original on 2009-02-09. Retrieved 2019-09-09.

- ^ E.A.D.Saunders (1988). Heat Exchangers:Selection Design And Construction Longman Scientific and Technical ISBN 0-582-49491-5

- ^ Hartman, A. D.; Gerdemann, S. J.; Hansen, J. S. (1998-09-01). "Producing lower-cost titanium for automotive applications". JOM. 50 (9): 16–19. Bibcode:1998JOM....50i..16H. doi:10.1007/s11837-998-0408-1. ISSN 1543-1851. S2CID 92992840.

- ^ Nyamekye, Patricia; Rahimpour Golroudbary, Saeed; Piili, Heidi; Luukka, Pasi; Kraslawski, Andrzej (2023-05-01). "Impact of additive manufacturing on titanium supply chain: Case of titanium alloys in automotive and aerospace industries". Advances in Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering. 6: 100112. doi:10.1016/j.aime.2023.100112. ISSN 2666-9129. S2CID 255534598. Archived from the original on Feb 4, 2024.

- ^ "Small Tube Copper Is Economical and Eco-Friendly | The MicroGroove Advantage". microgroove.net. Archived from the original on Dec 8, 2023.

cite web: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- ^

- White, F.M. 'Heat and Mass Transfer' © 1988 Addison-Wesley Publishing Co. pp. 602–604

- Rafferty, Kevin D. "Heat Exchangers". Gene Culver Geo-Heat Center. Geothermal Networks. Archived from the original on 2008-03-29. Last accessed 17/3/08.

- "Process Heating". process-heating.com. BNP Media. Archived from the original on Mar 16, 2008. Last accessed 17/3/08.

- ^ Wiehe, Irwin A.; Kennedy, Raymond J. (1 January 2000). "The Oil Compatibility Model and Crude Oil Incompatibility". Energy & Fuels. 14 (1): 56–59. doi:10.1021/ef990133+.

- ^ Panchal C;B; and Ebert W., Analysis of Exxon Crude-Oil-Slip-Stream Coking Data, Proc of Fouling Mitigation of Industrial Heat-Exchanger Equipment, San Luis Obispo, California, USA, p 451, June 1995

- ^ Domestic heating compliance guide : compliance with approved documents L1A: New dwellings and L1B: Existing dwellings : the Building Regulations 2000 as amended 2006. London: TSO. 2006. ISBN 978-0-11-703645-1. OCLC 500282471.

- ^ Epstein, Norman (2014), "Design and construction codes", HEDH Multimedia, Begellhouse, doi:10.1615/hedhme.a.000413, ISBN 978-1-56700-423-6, retrieved 2022-04-12

- ^ Heat Loss from the Respiratory Tract in Cold, Defense Technical Information Center, April 1955

- ^ Randall, David J.; Warren W. Burggren; Kathleen French; Roger Eckert (2002). Eckert animal physiology: mechanisms and adaptations. Macmillan. p. 587. ISBN 978-0-7167-3863-3.

- ^ "Natural History Museum: Research & Collections: History". Archived from the original on 2009-06-14. Retrieved 2019-09-09.

- ^ Heyning and Mead; Mead, JG (November 1997). "Thermoregulation in the Mouths of Feeding Gray Whales". Science. 278 (5340): 1138–1140. Bibcode:1997Sci...278.1138H. doi:10.1126/science.278.5340.1138. PMID 9353198.

- ^ "Carotid rete cools brain : Thomson's Gazelle".

- ^ Bruner, Emiliano; Mantini, Simone; Musso, Fabio; De La Cuétara, José Manuel; Ripani, Maurizio; Sherkat, Shahram (2010-11-30). "The evolution of the meningeal vascular system in the human genus: From brain shape to thermoregulation". American Journal of Human Biology. 23 (1): 35–43. doi:10.1002/ajhb.21123. ISSN 1042-0533. PMID 21120884.

- ^ "United States Patent 4498525, Fuel/oil heat exchange system for an engine". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ^ Croft, John. "Boeing links Heathrow, Atlanta Trent 895 engine rollbacks". FlightGlobal.com. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ^ Research, Straits (2022-07-06). "Heat Exchanger Market Size is projected to reach USD 27 Billion by 2030, growing at a CAGR of 5%: Straits Research". GlobeNewswire News Room (Press release). Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- ^ Kay J M & Nedderman R M (1985) Fluid Mechanics and Transfer Processes, Cambridge University Press

- ^ "MIT web course on Heat Exchangers". [MIT].

- Coulson, J. and Richardson, J (1999). Chemical Engineering- Fluid Flow. Heat Transfer and Mass Transfer- Volume 1; Reed Educational & Professional Publishing LTD

- Dogan Eryener (2005), 'Thermoeconomic optimization of baffle spacing for shell and tube heat exchangers', Energy Conservation and Management, Volume 47, Issue 11–12, Pages 1478–1489.

- G.F.Hewitt, G.L.Shires, T.R.Bott (1994) Process Heat Transfer, CRC Press, Inc, United States Of America.

External links

[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heat exchangers.

- Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger Design Software for Educational Applications (PDF)

- EU Pressure Equipment Guideline

- A Thermal Management Concept For More Electric Aircraft Power System Application (PDF)

Authority control databases: National  |

|

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning